I Paid Off $194k in Student Loans in Six Years. It Wasn’t Easy.

Table of Contents

-

Disbelief

In which I accomplish a long sought after financial goal and determine the need to reflect on how it came to be. -

Adventures in Aliens and Castration

In which I discuss a ruined scheme to bypass a formal education. -

"Deer", Dear Friends

In which I discuss the forces that led to my future financial burdens. -

The Price of Learning To Learn

In which I face the cost of years of eschewing education. -

A Mad Scramble Against Madness and Financial Reality

In which I struggle to navigate a tumultuous job market while loan repayments loom. -

My Chance

In which I am given the chance to overcome past decisions. -

Oblique Machine Dreams

In which I decide the best way to become an economist is to do everything I can to become a machine learning engineer. -

Sticking To It

In which I save a lot, and then dump most of it into my loans... -

Pay Off

In which I achieve my goal and think about what's next.

Disbelief

When I was 23 years old, I graduated college with approximately $150 thousand dollars in student debt. That year, as I faced what felt like my life falling down a financial cliff that I hadn't even realized I'd summited, I made myself a promise: I would pay all of my debt off before I was 30. I wasn't sure how serious the promise was, but it felt real. The joke was on the bank anyway—that was forever away.

Apparently not. I turn 30 in two months...

With all that money being owed, you'd think I wouldn't meet my goal. And yet, as of Sunday, July 16th the most unexpected thing happened: I did it? I actually paid off all of that debt and more. For the first time in six years, I am debt free.

While wonderful and financially freeing, that hasn't been the part that gets me. See, I've run the numbers in several different ways, and every time the same number comes up: $194,537.70. That's how much I actually ended up paying for a four year undergraduate degree. What happened to the $150k I mentioned earlier? Well, the best and worst part of finance happened (depending on which side of the deal you're on). When I took out my loans, it was 2012. The world was still coming down from the financial crisis, and rates for a private student loan were... high. 8% and above high. At the time, due to circumstances that I get into later in this post, I didn't feel I had much of a choice. And the result of that thinking is the number you see above. $194k dollars paid back in six years.

You may judge the amount I paid for my education (and rightfully so!), but I'm not the only one who dealt themselves a bad hand as a kid, or took burdensome loans in an attempt to get escape to a better life.

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, as of Q1 2023, Americans owe a combined $1.6 trillion dollars in student debt. And while delinquency rates have plummeted in the last few years due to a pause in student loan payments and interest rates (at least among public loans), don't expect that to last for long. Compared to their predcessors, 18-29 year olds hold the most student debt of any previous generation (see chart below). While many would prefer to ignore the plight of student loan debt upon this generation—answering the problem with whataboutism comparisons to mortgage debt and cold "they made their choice" sentiments—the consequence of ignoring balooning debt is a potential future economic crisis. After all, my student loan story is by no means indicative of the rest of the population of debt holders. But it is my story and one I'd like to tell.

So about the shit load of money I paid back...

I think of myself as a pretty astute follower of my own finances and even I didn't realize how much I'd sunk into those loans. The amount I paid off, uncomfortably close to 200k dollars, still daunts me (as if somehow $150k were any better?). It's bothered me so much that I've decided to write about my journey—how I came to sign onto these loans, the psychological and emotional weight they held over me, and my almost monomaniacal mission to study and work my way into a position to pay them off by 30...obliquely.

Admittedly, this post may not be the tried-and-true method of engaging with one's audience. Instead of writing a how-to post about "how you too can pay off your loans!", I much prefer to write a "how-did" post—as in "how did I even get here." For me, this story is an exploration of the choices I made that got me here and the obstacles I encountered along the way. It will be a lengthy post. For those of you who choose to continue to read, I hope you'll gain some insights and lessons too—there are certainly many to be gleaned.

Before I start though, I want to get ahead of the cynics out there. You know those feel-good stories about the person who pays off all this debt, only you're then to find out that they inherited a trust, or that their parents came in to help them out, or some other such convenience? I just want to get ahead of that: this will not be one of those stories. This all was truly paid off by me... by somehow scrambling to turn my life around.

Adventures in Aliens and Castration

I graduated my alma mater with a double major in economics, environmental studies, and around $150k in public and private student loan debt (that would soon balloon thanks to the magic of interest rates). I didn't actually want to go to college when I graduated high school. Despite being president of my high school senior class, I was a terrible student—deeply curious, but probably to the point of being depressed and therefore unmotivated. For a reason I was begged by every significant adult in my life to arcitulate, but that I could not, I simply wouldn't (couldn't?) do school work. No one could make me, despite many wonderful people's best efforts. On the contrary, I knew I was "ruining" my future with my inaction, but that was part of the point: I was cutting my nose to spite my face. If I punched myself hard enough (metaphorically) maybe things would change and my life would get better. Still, I couldn't truly understand how many doors would shut on me because of my choices. That would come later.

Upon graduation, as my friends were going everywhere from state schools to artsy liberal arts colleges to lauded Ivy Leagues, I was the only person I knew who simply didn't have a plan. Among a graduating class of over a thousand people, most of whom I knew (I was very social), I was thinking about maybe farming for a while? Honestly, I took a bit of pleasure out of it. The school I went to, although public, was in a Chicago suburb and known for being one of the best in the state. In my mind I thought about how it reflected badly on the school. "That'll show 'em!" or some such other nonsense. In hindesight colored by life experience, it's easy to see how arrogant and emotionlly immature I was. To think anyone thought about me at all, beyond the caring teachers who got me over the finish line of high school graduation, was a categorical mistake. Plenty of students do not succeed in high school. It's par for the course.

As I said, as graduation approached and friends were talking about the colleges they were going to, I thought about farming. I had built up farming in my mind for quite some time. It was practical. Without it and the energy food provided, humans could not survive. It made all the existnential sense in the world to me. Even though I had no relationship to farming growing up (maybe that's evident from my content so far), it called to me. From some connections, I learned of the concept of WWOOFing—World Wide Opportunities in Organic Farming. The way I describe it is it's the Craglist of farming. Farmers post about what work needs to be done and, in exchange for doing that work, agree to host these laborers for a season or so. I looked for what was probably 20 minutes, found a post, called the gentleman who ran the "farm" (more on that soon) and convinced myself this was the move to make.

I settled for a farming position in Hawaii. I'd never been, and indeed had not really thought about Hawaii much before. But it was the furthest place in the US I could go that was both feasible enough to convince my parents of, and that I could afford with my savings. I bought myself a ticket (around $600 in 2012 dollars) and was off by late summer.

The farm saga was a fiasco, as you might imagine. Here I'll just state the cliff-notes.

In late August,/early September I arrived on the Island and was picked up by my host's associate who I'd never heard of before. Good start. Always get into cars with your host's "associate".

The associate took me to a get a "drink" at a seaside bar, only to learn I was 18. I got mango juice. We got to talking a while. As the conversation progressed, I slowly averted my gaze to the water, trying not to look at my new associate as she regaled me about her numerous abductions by aliens. Indeed, it was a regular occurence and she could (and did!) tell me all about the interior of the UFOs, about how we're not alone, and more. Obviously I was not comfortable, but I played it off by asking such light follow-up questions as "what did the aliens look like" and "oh, I see. And what did they do to you then?"

After what felt like forever, the conversation subsided and she drove us to my host's house up on the side of a mountain, next to a large rainforest. But alas, what was this? There was no farm to be seen! Ah, it turned out that my host had never farmed before, and that I was to make the farm, among other activities. This was not we discussed over the phone, but okay, fair enough. It wasn't the plan, but I wanted to be pushed physically, to pay for the mistakes of my past and to earn my place in the world. This could work, maybe...

By nightfall, I inquired as to where my room was. Duped again! Despite what I had been told, there was not actually a room for me. Instead I was provided a massage table to sleep on while my tent, which apparently I was to live in, was prepared... A tent could be nice? So long as you could get past all the mosquitos and the rain that periodically falls in rainforest climates...

As I settled in to my massage table that night, ready to sleep, my host came up to me and asked for my help. It would seem his three large black dogs had gotten out "again". And wouldn't you know it, they escaped into the rainforest! You know, the one with poisonous catepillars. Don't worry, I was provided a small flashlight. Thus began my attempt to navigate the rainforest to find his dogs. Eventually they returned on their own—though it would have been nice if I had known that earlier as I continued to search...

Eventually I returned to back to my trusty massage table to sleep, uncomfortable, afraid of what I had gotten myself into, trying not to give in.

By the next morning, I couldn't take it. I called my sister, Nikki. I was hestitant at first, but that soon gave in to the truth: I was deeply uncomfortable, I made a mistake, I didn't want to give in but that I thought maybe I should come home... I was so mad at myself, I hated being a person who gave up but this place was seriously off. After some vigorous debate with my parents, with some strong-arming from my ever-faithful sister, it was determined I was to come home.

The next morning, I broke the news to my would-be host. To which he not so subtly responded, among other things, that a worse person would "castrate you". Thank goodness he wouldn't do that...right? We eventually agreed that he would drop me at the airport if I paid for gas (and that I would arrive intact? It was never made clear.)

"Deer", Dear Friends

After a string of connecting flights, I made it back home. My one and only plan a total failure. The next few months were a blur of self-flagalation and isolation. I barely showed my face to my family, and certainly not my friends. I didn't know what I was going to do with my life. The feeling of failure permeating my thoughts.

I wrestled with a bunch of potential next steps including shoe cobbling, guitar making, and of course the military. Unbeknownst to my parents, I visited the marine recruiter and navy recruiter multiple times. Let me tell you this: there are few better salespeople for the lost than the military (and probably the priesthood but I digress...). Ultimately, I didn't sign up. I was certainly interested. It would have been a release of pressure—a means with which to structure my life. But as with many choices in my life, it came down to not wanting to put my mother through more stress than I already had.

So, none of those options worked out. During some of my free time, besides escaping my reality by watching Doctor Who, I would simply walk. I didn't have a direction or a purpose. I just needed to get out of my room, and therefore my head. There was a forest by my house, just west of us down the road. Eventually my walks would take me there. It was tick-ridden. There were few well-trodden paths. But it was the closest "escape" I felt I had access to. As I began to map out the forest on my walks, I eventually came across a small, graffiti-ridden bridge with train tracks running across it. It appeared many youths used the small bridge to get away from it all (or to smoke and drink...). The bridge became a frequent stop on my walks. I would walk to the bridge, sit on the edge, dodge the train, and stare at the water of the North Branch of the Chicago River as it trickled by.

The West of which I speak is but another name for the Wild; and what I have been preparing to say is, that in Wildness is the preservation of the World.

Walking, Henry David Thoreau

Time slowly passed, like that trickle of water, and I felt life and friends were moving on without me. Except one friend. Her name was Alex. We went to high school together.

Alex was a nerd like me, and despite being downstate at UIUC studying engineering, she would text me to talk. Often I would pepper her with questions about the Doctor Who universe or vlogbrothers, asking for her theories or why certain things occured. But beyond simple chatter, she would also encourage me to go to college. Lightly, politely, in a way wholly unique to her, she would simply tell me it was a good idea with a level of stoicism and certainty that I had nowhere else in my life. It was an attractive prospect. I didn't know what she saw in me, or how she could know college was a good idea. But the idea of having structure like college could provide me was as appealing as an oasis in the desert. I just couldn't understand why she said this. She knew how bad of a student I was only a few months ago. And yet, she encouraged it. I didn't say yes right way, but I did say I'd think about it.

This continued for weeks. I would walk around, look into different opportunities, walk around, text Alex about some some show or YouTube video we were into.

One day, I was walking the forest west of my house. It was late fall. I remember the orange and red maple leaves that matted the forest floor. As I made it to the bridge hidden in the forest, leaves crunching under my feet, I suddenly decided I would cross it and descend onto the other side of the river tributary. I hadn't done this before, but that day felt different. As I walked new, unfamiliar paths, headed in no particular direction, I looked up. In the distance was a deer. The deer was standing just on the other side of a brief bend in the path—a few scattered trees and bushes between us. It was staring at me, as deer are wont to do. I stared back, thinking it would eventually move. For a while we stood like this, silent in the forest. But it didn't move. So, slowly, I began to walk toward the deer. Still it did not move.

Then he was aware of the wilderness itself, not as the background frame of earth and foilage in which he lived, but as a sentient, constant being…

Go Down Moses (The Bear), William Faulkner

As I got to the bend in the path that I'd seen from a distance, I came to a standstill—just a few trees and foliage between the deer and myself, the deer standing whisper still. We stood as we had been, staring. I decided I would follow the path briefly around the bend, past the boughs of trees, and see if I could walk up to it on the other side. As I walked around this brief little bend, the deer's anticipated position returned to my line of sight. But what I saw was...nothing. The deer was gone. The bend wasn't significant at all, I thought I would have heard it run away. But it was simply gone.

Slightly confused, I walked up to where the deer had been and stood there, thinking. After a few moments, I heard a creaking sound. I looked around but couldn't pinpoint where it was coming from. The creaking sound started to get louder, and louder, until it was very significant. I swivled around desperately trying to identify what was happening until a loud crash! Right where I had stood staring at the deer, on the other side of the brief little bend, a tree had crashed to the forest floor. Like, a legitimate tree! In that exact spot. There was no wind, no movement of any kind that I could detect.

I'm not sure how anyone else would react, but to me this was very absurd and amusing. Laughing to myself, I looked around as if to say "did you see that" to the nobody that was around me, when I saw a deer, the deer, far down the path, across the river tributary, staring at me once more. I looked back at the fallen tree, and then looked back to the deer as it began to walk away.

Did that deer try to kill me? Was it trying to tell me something? I don't think think so. It was very probably just a coincidence. What I do know is that I also had had enough. As the deer started to walk away, I said aloud, flatly to the universe: "fine, I'll go to college."

The Price of Learning To Learn

College was four years of my life and a rich enough experience to take up many pages of writing. But I'll try to keep it short. What's important to say is this: before college I had not truly learned to learn. Thus far I have characterized high school as anomolous in my education career. But the truth is, I had always had an adversarial relationship with education. I remember in fourth grade I told my teacher that I wasn't going to do the work any more because I wasn't happy. In the years before and after, I would often act out in class, or else completely withdraw. One time I came to school dressed up in "goth" makeup. I was told to take it off almost immediately (I threatened to sue...it did not work).

This pattern of withdrawing from my education had followed me on and off throughout the rest of my middle school and junior high experience. Sometimes I would delve deeply into my education—investing into it all that I hoped it could do for me, hoping to escape. If these periods lasted long enough, I'd be fed into advanced placement courses to talk Freud or math, or some such thing. But it never lasted. I would simply withdraw again.

Because of this pattern, which continued into high school, by the time I started college I had never really had learnt how to learn. College changed that in myriad ways.

I started college in the winter of 2013. That fall I had decided to attend a small liberal arts college. That may seem like an insane (and expensive) idea, but unlike my WWOOFing experience, there was real thought put behind it. First, despite sometimes acting out or not doing the work, I had always bonded with my teachers, probably because my mother was one. By being able to foster relationships with my professors, the hope would be that this would sustain my academic motivation (this is exactly what happened). Second, I did well in smaller, more intimate communities and figured this would sustain me in college (this also turned out to be true). Finally, Lake Forest College, the college I ended up attending, was willing to admit me the very next semester, and I had to get out of the house.

The price of this deal was, as we now know, high. Below is the semester by semester breakdown of my loans (public and private) from 2013-2016.

Because I didn't come from money and because school was so expensive, public loans wouldn't be enough and I had to borrow from a large, private loan provider. I won't name names directly. Let's just say the name rhymes with Discover...

Breaking things down, my public loans came to a seemingly hefty $27,000 dollars. Of course, then you look at my private loans and you realize that wasn't anything. Altogether my private loans came to $122,001.20. Together that's a total of $149,001.20 taken out over four years (without interest).

So, briefly, what did this get me?

I left college in Dec of 2016 a different person than I started. When I started college I was neither driven nor fully educated. Thankfully, blessedly, I met professors (too many to name) that not only inspired me with their knowledge, but gave me the time and energy enough to help me lift myself out of the hole I dug for myself. When I left college, my intellectual motivation was self-sustainaing for the first time in my life. It was the most free I had, or have, ever felt.

This was reflected on paper too. During college I travelled and lived in Southern Africa to study economics and human trafficking. I even got to "farm" of sorts, as I became deeply involved in prairie and ravine restoration projects on and off campus. I graduated Lake Forest College in 2016 with multiple scholarships and distinguishments to my name including graduating cum laude and earning honors and awards for my senior thesis.

My successes were reflected internally as well. I had entered college not knowing what I wanted to do. By the end of my first year, I knew with every fiber of my being that I wanted to become an economist. In the succeeding years, I did everything I could to work to make this happen.

Then, one day, like a record scratching, the party was over, and I was back home where I started.

A Mad Scramble Against Madness and Financial Reality

After graduation, I was scared. Suddenly I was back home in my same childhood room. The same place I had spent so many years in unproductive isolation. The place where I had lain in bed and slept throughout most of high school. All the work I had done over the last four years to become a better, different person—to actually do instead of just think—would it come crashing down? Did college really not change my life like I'd hoped it had?

The truth, as ever, was complicated. What I couldn't know as I put my bags down, staring into my old room in despair, was that over the next eight months I would engage in a mad scramble against the financial reality that the last four years of loans had wrought me.

As soon as I got home, I told myself that I had to act. I needed to apply all of my self-sustaining motivation that I had learned in college, that I had saved up my whole life, into applying for jobs. I was going to dig myself out my situation using pure grit and determination.

I spent the next 4 months trying to get a job. Every day was the same pattern: I would wake up at 6 am, go on a run, come back, and spend the next 8 hours searching for jobs. It was the same process over and over again. First I found a job on some website, then I would write a cover letter, then apply. Rinse and repeat. During these months, I barely left my room, talked to my family, or contacted my friends. In part it was because I was embarrased about not having a job. In part it was because I told myself the only time worth spending was time working toward my goal of independence—to get back to the life I left at school.

I suspect I sent hundreds of applications, with less than a 1% hit rate for callbacks. Not even Starbucks would call me back. I remember mustering up the courage to walk into my neighborhood store one day. I asked for the manager and told her that I would like to apply in person to demonstrate that I'm ready to show up and work hard. Her response was to go back and apply online like everyone else. Like most of my applications, I didn't get a follow-up call.

I tried not to be deterred, but it was hard. Even now I feel that familiar lump in my throat, that creeping pressure to get out from under the rock of my own making and the knowledge mourning of a lost academic community in which I felt I belonged. I didn't give up though. I told myself that almost any obstacle can be overcome with determination. But the ticking clock of all that debt was looming over me like Damocles' Sword. I had to start earning money.

One day, out of desperation, I reached out to the career center of my alma mater and set up a meeting—maybe they could help me? When I met with a career counselor, this is what he told me: almost every job he ever got was through knowing people—that he hadn't applied to a job in decades. I didn't know what I felt more fiercely, frustration at what I'd just been told in the face of months of trying, annoyance at the college for not helping me more after all the money I'd spent, or desperation about my situation.

For obvious reasons, it was frustrating to hear. But despite being a bitter pill to swallow, I forced myself to take something from what he said: networking was critical. Maybe I could get a job that way? I tried, I really did. I reached out to people I thought could be good to speak with, but the perverse reality of networking is that if you have a good network, you're probably not in the position of being desperate for a job in the first place. Well, I was in that position. I had a handful of "coffee" sessions with various connections. But they all led to nowhere.

It was starting to get close to when my repayments would begin. I wasn't clear on how much I would need to pay every month, but I knew it would be significant.

Eventually, my mental state began to crack. Months of self-imposed isolation, nonstop work, and stress had caught up with me. College was so intellectually thrilling, so freeing, and I was good at it! There I could engage at a pace that suited me, while surrounding myself with interesting people and professors. There I had become the person I'd always wanted to be. Yet so many companies, organizations, and schools which I admired ignored my applications or worse, saw the college on my resume and laughed at me. Yes, this really happened in the case of a particularly entitled Northwestern professor I had attempted to network with.

The resentment began to build.

It was finally hitting me, the force of the doors I had pre-emptively shut on myself as a kid were finally starting to impact me, as if the delayed shock wave of a particularly distant and powerful bomb.

I was out of breath emotionally and I couldn't tread water any longer. I remember calling my sister one day, crying. I didn't even know what to say. It was all too much. I ended up just saying "I'm sad." I knew it was an understatement, but I was just too emotionally exhuasted. It had been months of applying 8 hours a day in self-imposed isolation. I just needed help. I just wanted to prove myself. Nikki supported as she could, as she always has. But I didn't make it easy on her. She had supported me before college and now she was left supporting me emotionally after college too.

Feeling like not even my family could support me, I only cracked further. One day my siblings, all older than me and moved out, come home together and were downstairs. My mother came to my room to ask me to join them. She found me in a chair, in a fetal position, weeping. I told her I didn't want to go crazy, that I was trying my best. She of course supported me and brought me down. But this was perhaps my lowest point.

Obviously, in hindsight I understand the situation a bit more clearly. The fact is, joblessness enduced mental-health issues are a special kind of hell. We are such a job-defined society, to not have a job—even a (wrongly) low-regarded service job—can force one to consider themselves less-than. And if you have people who depend on you, I can't even imagine how desperate that would make a person.

But it's also more fundamental than that. It's about a sense of competance, and meaning, and wanting and trying to work but not be deemed suitable enough to do so. It's why I especially feel for the job-seekers who have been on the market for some time. That process takes a toll on you in ways hard to describe.

But to me it was also about how easily the echoes of our past mistakes as young adults reverberate with us, even when we do everything we can to overcome them, to make up for them. Many children and young adults have to be able to make mistakes, to stumble and learn and grow. Unfortunately, the consequence for those of us who make the mistake of having mental health problems during the critical period of one's education can be shutting the door on potential future opportunities and feeling forced to take out crippling loans. But it can also be more severe than than the choices I made: it can be drugs, crime, jail, or worse.

During this experience, one of my fiercest wishes was for a world in which the mistakes we make as young adults are not made to follow us throughout our lives. The best way to achieve this, I think, is simply to afford young adults a chance. Just give them a chance, and see if they take it. Some wont'! But many will.

My Chance

One day, four months into my monomania, I was granted a blessed respite and received a rare follow-up email for an application I had sent. It was from the Chicago Botanic Gardens. I had applied for a "Restoration Ecologist" job in their prairies. As I mentioned, in college, I had spent much of my time building prairies on and around campus. It was some the most fulfilling, hardest work I've done in my life. There I was finally able to push myself physically, to improve the world while also making up for the mistakes I had made.

I ended up getting the job. It paid something like 12 dollars an hour. In reality, it was mostly pulling weeds all day. But at least it was a job, I thought. With a few weeks until my loan repayments would begin, I figured I'd build a buffer of money before my payments started. Daily I'd walk the prairies and dutifully pull weeds, spray Glyphosate (a carcinogenic weed killer), and identify and tag troublesome plants for future mitigation efforts, the words of the environmentalists Aldo Leopold and Emily Dickinson running through my head, lightly filling the space in my mind where meaning was needed to push me forward. With their words and with the knowledge I was being paid, I could withstand the ticks, the sun, and the labor. So I thought.

To make a prairie it takes a clover and one bee,

One clover, and a bee.

And revery.

The revery alone will do,

If bees are few.To make a prairie (1755), Emily Dickinson

When my loan repayments began, a few weeks later, I was in for a shock. My private loan payments came to $1106.42 per month, my public loans $387.02. Altogether, I would owe $1493.22 per month. I did the calculations in my mind. At a 40 hour work week, I'd earn around $1902 per month before taxes. Subtract my loan payments, and I'd take home around $425 per month before taxes. On the one hand, great at least I'd be able to pay off my loans. On the other, I'd never be able to leave the garden, let alone my parent's house, at this rate. It soon became clear to me that the only way I was going to get out of this mess was to get a better paying job. I wasn't done with the job application process.

My schedule only shifted slightly with my new job. Every day I'd wake up, write a few applications to better paying jobs, go to work, pull weeds, come back, eat dinner, apply more and sleep. This continued for 4 more months. In the meantime, I dutifully went to work. Luckily, I had a colleague who ended up becoming a close friend. Her name was Jess and she was a very patient individual.

When you're pulling weeds in the sun, you mostly have audiobooks or each other to talk to. Often I would talk to Jess about my favorite pastime: economics. I know it sounds annoying, and maybe it was, but these were (are) my genuine interests and Jess didn't seem to be against these conversations. I would talk to her about different aspects of economics I was interested in, different theories, how they applied to the books I was listening to or to world events, all while we pulled weeds. Jess was a great listener. I tried to be the same for her.

This process continued week after week. Jess would talk to be about her interests (biology) and I would talk about mine. Until one day, Jess told me that I needed to stop restoration. It was clear that I should be working in economics and not restoration ecology. I told her I had been trying, but she told me that wasn't enough. I needed to take a risk and devote myself to it. I thought about it and agreed.

I talked to my parents and they supported me. I resigned from my position at the gardens, despite the risk of running out of funds, and devoted myself full time to getting a better paying job in economics. And wouldn't you know it, a few weeks later, I landed one.

The job, if I agreed to take it, was as an economic researcher at Arity, a telematics "startup" within the Alltstate family. My job was to write internal white papers about different subjects relating to Arity's products so that managers, VPs, and other key decision makers could understand the landscape better. I heartily agreed. For my work I would be paid the unimaginably high income of around $50k a year. It was a dream come true. I threw myself into the work. There were no guidelines or deadlines beyond just writing something useful for the execs. It was perfect—just the amount of oversight I wanted (none). By October 2017, three weeks into my new job, I wrote a 24-page single-spaced paper that reverberated around the company about the economic conditions that led up to the use of rideshare in the American economy.

The positive feedback fueled me. My next paper, part one of a two part report, I released a few weeks after that. It was a 38 page single-spaced diatribe about the impending semiconductor crisis and labor and parts shortages of American motor companies. Part 2, released in January 2018, balooned to 78 pages single-spaced (table of contents below). It covered everything from the history of automobile use in America, millenial debt (I've been on this train for a while), spatial and urban economics, and more. As I've said, I was monomaniacal. I wouldn't stop. All I wanted to do was to prove myself, to push myself.

By April 2018, my final report was published (less fancy table of contents below). At this point I came to realize that I was pretty much writing for myself. No product manager was going to read an 88 page, single-space report on the origins and uses of Pigouvian taxes on traffic congestion mitigation, regardless of how well written it was. One day I looked up from all my writing and realized my data scientist colleagues across the way were simply more impactful than me. It became clear to me that it wasn't economic report writing that was going to affect change, but modeling.

Far from an inconvenient reality, I viewed this as good news. After all, there was a lot of math and modeling in data science. And seeing as how I wanted to shore up my background in math as much as possible—having only really started getting into it during my junior year of college—maybe this would finally get all those grad school economics professors to look my way when I eventually, some day, applied to grad school. Suddenly I saw it. This was an oblique means to my ultimate ends: to one day become an economist.

It was time to learn programming and machine learning.

Oblique Machine Dreams

As it turns out, all the monomania that I had put into college, into applying to jobs, and into my research at Arity, had helped me build a very useful habit: studying programming and ML. Over the course of the following weeks I taught myself R, and then Python when I was told R would hold me back. I started to try to integrate coding into my work as best I could—anytime there was a task, I'd try to leverage my newfound skills to practice, and to get work experience for my resume.

The process of becoming a data scientist and eventually machine learning engineer was not smooth, nor marked with very many clear boundaries that officially declared my progress. I'm sure I will write a more detailed post in the future about how I got into this field. What I do know for certain was, like college, surrounding myself with individuals far more knowledgeable than me was very helpful in keeping me curious and motivated.

At work we had many data scientists and engineers. I tried not to ask them too many questions (though it's hard to help yourself sometimes), but instead surround myself with them and to listen in on what they were working on, what they had trouble with, and what problems interested them.

From my experience, the best thing you can do is to find one or two individuals in particular that you like and who seem to like you, and ask them to mentor you. One day, I found mine. His name was (is) Justin. He came into work with a very "loud" Dragonball Z anime hoody on that stood out among all the button down shirts at the office. We got along well. He was down to Earth, but clearly sensitive like me. Eventually he was assigned to the team I had been working with, and I took my chance to ask if I could shadow him a bit and learn about data science. He was happy to oblige me. More than teaching anything in particular, it was great just to have the kind of guidance and perspective he provided. He likely doesn't think he did much for my career but I will always be grateful to him.

It wasn't just studying at work that got me prepared, however. There was a lot of outside work that had to be done. When I was at home I spent a lot of my time reading and studying. Every day on the train to work, at lunch, on the train back, at home, and over the weekend, I would study. Luckily this stuff actually interested me, so it didn't get too overwhelming. Data science and ML work was so satisfying because you immediately saw the consequence of your work—the feedback mechanism of coding is one of its most attractive features.

After a few months, I was very comfortable in this world. That was good timing too, because one day Justin brought me and the team into a conference room to talk. He was leaving for a different job. I was devestated. I cared a lot about Justin. I hadn't yet embraced the cold, distant relationship style that allows people to remain unmoved when a colleague suddenly stops apppearing day after day. But I also learned a lot about how to approach work and work-related problems from Justin. I knew there simply wouldn't be another mentor like him.

Around that time is when I decided to start looking for another job myself. It had been two years or so and, although my work at Arity had clearly shifted from research, to analysis, to data science and ML, my pay did not reflect this. I learned from Justin that this had to change and it wasn't going to change there.

A few months later, I got a. job. My first "official" data science job. With some negotiation help from Justin, who had kindly kept in communication with me, I was able to more than double my salary. I didn't even think that was possible to do, but it was. Suddenly I realized that my goal of paying off my loans while pursuing my own interests might actually happen.

Sticking To It

The next few years brought more work, more ML related problems and solutions, and different jobs with still better pay still. All the while I would simply grind, study, and save. I wasn't in the same financial position as when I graduated, but still I remained motivated to break the chains of this debt.

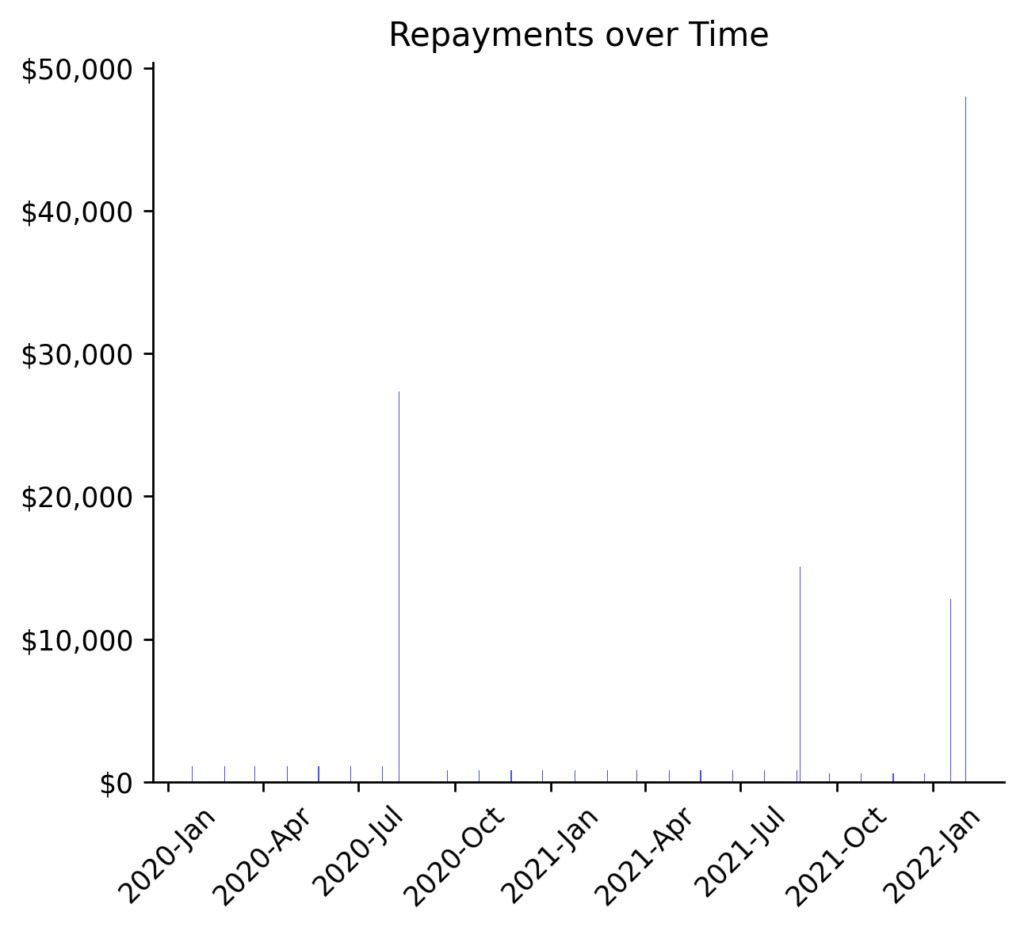

My strategy, if you want to call it that, was relatively simple: I would ensure payments were made on time every month, while saving the rest of my paycheck. I have a sample of these payments down below. After a few years of saving for emergencies, I would accumulate leftover savings. Eventually savings would accumulate enough such that I could use it to remove a chunk of debt. Then the process would start over again.

You can see a sample of this process in the chart below. Strategically, I would throw these chunks of savings at the loans with the highest interest rates and attempt to pay them down first. Ideally, I'd pay off an entire loan so that my monthly payments would shrink too, relieving the pressure I felt month to month.

Over the years I would refrain from spending much on anything—I was busy working and studying anyway so there wasn't much to spend it on. Then I would commit bursts of $15k, $25k, even $47k at once, just to get rid of the debt. Admittedly, the day I paid back $47k at once felt a bit weird. But it came with a greater sense of freedom, so that was nice.

Finally, belatedly, when the debt was whittled down to around $38k I realized that I should probably refinance my loans so they didn't have such high rates. Folks, if I can suggest one thing, it would be to look into refinancing your loans when rates are low. There is literally zero downside for you. I'm sure I could have saved upwards of $20k this way.

Maybe six months after I refinanced my loans, finally shrinking interest rates from 8% to 3%, I paid off my loans entirely.

Pay Off

As I've said, I am now debt free. Frankly, the journey of paying off these loans felt far more significant to me than the final act of paying them off. I've been asked: now that you're debt free, how do you want to celebrate? I haven't come up with an answer. Maybe I don't feel like celebrating. It was an unreasonable amount of money to pay off. But perhaps more simply than that, maybe it's just that I feel gratitude that I was even able to achieve this. I've felt for a long time now that hard work pays off, if you're willing to put in the effort. I am not saying that I believe everyone is able to work their way out of their problems, but I am saying I am grateful I was.

My journey isn't over, however. I love my career so far in machine learning and don't plan to stop pushing myself. I'm even applying my research background to writing reports on Large Language Models for O'Reilly Media! I'll also be teaching an Introduction to Machine Learning Course at the Argyros School of Business & Eeconomics at Chapman University this Fall. And I still haven't closed the book on the possibility of grad school in economics. Crazier things have happened, like, for instance, paying off $194k in debt in six years.

A final note: In 2020, as the pandemic began to proliferate around the globe, I had the honor of being my friend Alex's witness to the signing of her marriage contract (Ketubah). During that wonderful, intimate ceremony, as friends and family were giving words of blessing and thanks to Alex and her husband-to-be, I was able to take a moment to publicly thank Alex for all she'd done for me, for the belief she showed in me, and for the impact she's had on my life.

What an extraordinary piece of writing: part memoire, part economic summary of the (don’t get me started) criminal enterprise of the higher education business, partly the story of paying off your debt, and mostly the story of an unfinished unique intellectual journey. This is powerful and authentic writing. But about that deer: far from trying to kill you, it actually saved you. Perhaps it could hear the tearing of the wood inside that tree? Perhaps it was your patronus? Or perhaps I am too immersed in H.P.!!! I won’t linger on the agony of those earlier educational years, but when you were ready to learn, you landed in your right place. To your credit, you thank so many of those who have guided you on your way. Yet, everyone reading this account can see how much of your success owes to your inner strength and honesty. Your entire account speaks to the value of a Liberal Arts education, if we are truly listening…and you were.

Keep learning. I know you will. And devote as much as your achievement as you can to growing the good in the world. We are all so very proud of you.

Terrific writing. Made for an excellent read. Felt like I was right there with you along for the ride.

Thanks for the write up

best of luck,

Ben, I had no idea about your journey, I’m happy to have read about it now. Every once and a while I remember what you told me when you were moving out of CY after graduation, paraphrasing here, I won’t say never change, but do change for the better. I liked it, it was on par with the image of who you were I had in my head, someone thoughtful. I’m happy for you.